ICD-10 is on its way. It may be off in the distance, a tiny speck of a locomotive's headlight for now, but ICD-10 is coming, gathering speed as it barrels toward the Oct. 1, 2015 compliance date.

And you can expect a couple of ambush attempts. Most recently, U.S. Rep. Ted Poe (R-Texas) introduced legislation for a second time that would ban ICD-10 implementation. This is not surprising since the Texas Medical Association continues to advocate for the repeal of the new code set. Poe previously had introduced a similar bill in April 2013. But anyone who follows the legislative process will tell you that his current push for a repeal is dead on arrival.

Your best bet at this time is to get out of the way to avoid calamity. If you've been on board all along during the ICD-10 journey, you and your organization should be in good shape. If you're just now getting on board, you'd better hustle. Come the first of October, an estimated 10 to 12 million claims are expected to drop on America's aging healthcare infrastructure. Good luck getting paid.

So don't expect a last-minute reprieve. Don't look to the heavens for a hopeful sign that there's another delay waiting in the wings, ready to save you. The Coalition for ICD-10 has monitored with machine-like precision blog postings, congressional hearings, association email campaigns, and legislative briefings for any hint of a further delay. Even the American Medical Association (AMA), long a foe of implementing ICD-10, has backed off, according to most analysts who also report that the AMA successfully championed a permanent fix to the sustainable growth rate (SGR) formula. When docs get paid, everyone wins.

The last possible challenge to ICD-10 was the widely watched and giddily reported passage of H.R. 2, the Medicare reform bill that passed in both houses of Congress without any language to delay ICD-10, as everyone so vividly remembers back on March 31.

Yes, it's true, you could get struck by lightning before ICD-10 is delayed. And, yes, there's a code for "struck by lightning."

Look Out: ICD-11 is Coming!

Rising above the fray and its obvious distractions, progressive hospitals, physician practices, and health systems already are looking ahead to ICD-11.

"The good news for the U.S.," World Health Organization (WHO) official T.B.

Ustun noted during an April 24 edition of Talk-Ten-Tuesdays, "is that whereas

previous switches from one ICD iteration to the next were tantamount to wholesale

changes to the coding sets used around the globe to collect data on procedures,

conditions, and diagnoses, the leap from ICD-10 to ICD-11 is expected to be

a more gentle ride-even if the introduction of the newest version is still years

away."

Actually, some experts are predicting that completion of ICD-11 should occur

in 2017, just two years from now.

"In a sense, (for) the ICD-11 digitalization, with a few tweaks, we can make

it a retrofit to ICD-10-CM. So my recommendation would be to go to (ICD-10)

as soon as you can, but start 'elevenizing' it now," Ustun said. "Sorry for

the new verb; what I mean is, think of the benefits of ICD-11 and build them

into your system, day by day."

In the meantime, ICD-10, still the law of the land, proved its efficacy throughout

2014 and into the first half of 2015. For when detractors were chortling over

some of the more exotic ICD-10 codes (think, "hurt walking into a lamppost -

W2202XA"), there were also codes for diagnoses for conditions that were serious

enough to make national and even international headlines.

At ICD10monitor.com, we sought to link major health news stories with ICD-10

codes. You'd be surprised at specificity in these real-world crises.

Ebola Exposes Vulnerability

Who can forget the images of white ambulances arriving at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta, captured by television news helicopters hovering overhead, documenting 33-year-old medical missionary Kent Bradley walking under his own power to be admitted-the first American to contract the deadly Ebola virus.

At the time, the crisis shook the very foundation of America's healthcare system. We were the first to break the story of the issue relative to ICD-10.

That was back in August 2014. Nationally recognized healthcare consultant Gloryanne Bryant reported for us that ICD-9-CM data had always been utilized for bio-surveillance, with infectious diseases such as the West Nile virus, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), and Ebola being great examples. In addition, the expansion of disease surveillance and management was global, not just something being done in the United States.

Bryant reported that there was no ICD-9-CM code specific to the Ebola virus. On the other hand, ICD-10-CM has the ability to list "Ebola virus disease" in the alphabetic index and directs one to look at code A98.4 (note that this is not under a fever symptom or term).

"In the ICD-10-CM tabular, you find the three-character category as A98 Other viral hemorrhagic fevers, not elsewhere classified," Bryant wrote. "Then you'll find the specific entry for code A98.4 with the actual title (description) of Ebola virus disease, (which) does appear to be more specific than ICD-9."

Little did we know then that Ebola would become such a developing story. This was especially the case when on Oct. 8, 2014, Thomas Eric Duncan died due to the virus in a U.S. hospital. At the time, Duncan's tragic story became a lightning rod for fear, rumors, and misconceptions in politics, policies, and everyday life. Duncan, the first patient to be diagnosed with Ebola in the U.S., had recently returned to this country from West Africa. His presenting at the emergency department at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas with flu-like symptoms and premature discharge focused attention on the best practices for dealing with infectious diseases.

Robin Williams: Depression No Laughing Matter

The Aug. 11, 2014 death of world-renowned actor and comedian Robin Williams came as a shock to millions. Like many dealing with major depression and other mental health conditions, Williams suffered in silence. His diagnosis was just a little-known fact in a very celebrated and public life.

Mental health diseases are no laughing matter. Neither is the documentation and coding of these cases in ICD-10.

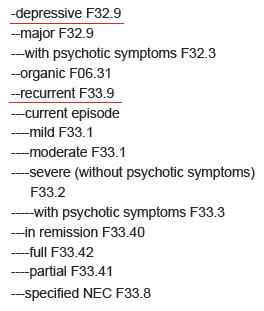

"In the ICD-9 coding world, code number 296.20, major depression, single episode, unspecified, is used, with a secondary diagnosis a CC," wrote Kimberly Janet Carr for ICD10monitor. "With the conversion to ICD-10, because 296.20 is an unspecified code, it loses its value as a CC and will translate (along with ICD-9 code 311, depressive disorder, not otherwise specified) to ICD-10 code F32.9, major depressive disorder, single episode, unspecified. This code is not a CC in the ICD-10 world. In order for 296.20 to maintain its value as a CC, the physician must document the acuity of the major depression."

Carr also noted in her article that, for example, the physician must document whether depression is mild, moderate, severe, or severe with psychotic features in order to qualify for a CC; he or she cannot translate to the same code as depression not-otherwise-specified (NOS).

According to the DSM-5 (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders), which is published by the American Psychiatric Association, major

depression is defined as having one or more major depressive episodes in a period

of two weeks or more, in a case in which a person has either depressed mood,

the loss of interest or pleasure in nearly all activities, and at least five

or more of the following symptoms nearly every day:

- Depressed mood, by a person's own report or as observed by others;

- Significantly diminished interest or pleasure in all or almost all activities

most of the day;

- Significant change in weight not due to dieting;

- Insomnia or hypersomnia;

- Observable physical agitation or lethargy;

- Fatigue or loss of energy;

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt;

- Difficulty thinking clearly or concentrating or indecisiveness; and

- Regular thoughts of death or suicide (either unplanned, planned, or attempted).

To meet clinical standards, these symptoms also must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

The major depression must also not be caused or explained by the following:

- Effects of drugs or medication

- A medical condition

- Bereavement

Per the DSM-5, depressive disorder NOS is a more general category of depressive

disorders that do not fit the descriptions of major depression.

Examples of this diagnosis would be:

- Having episodes of two weeks or more with the symptoms matching fewer than

the five described above criteria for major depression

- Having episodes of two days up to two weeks bearing similarities to a major

depressive episode, at least once a month for at least a year

To meet clinical standards, these symptoms also must cause significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

As detailed above, the DSM-5 definitions of major depression and depression NOS describe two very different types of patients.

Those diagnosed with major depression should have a higher severity-of-illness score and also will be more resource-consumptive (close observation by nurses, etc.) versus those diagnosed with unspecified depression. But without the specific documentation by the physician, these two very different diagnoses will be captured with the same ICD-10 code.

Coders should work closely with clinical documentation specialist and physician teams to understand the differences and ensure that correct documentation is included in the chart. By working together, these three teams will help secure correct reimbursement for their organizations under ICD-10.

Williams's death also brought to light important health information management (HIM) concerns regarding privacy. Celebrities may be even more at risk for shunning treatment due to privacy concerns than the general public. In addition, unauthorized viewing of celebrity records causes hospital staff terminations.

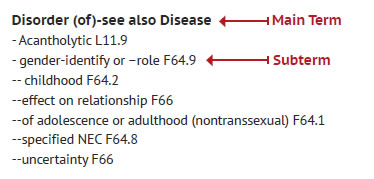

Gender Identity Dysphoria

The tragic suicide of Leelah Alcorn of Kings Mill, Ohio, the 17-year-old who ended her life in part to bring attention to bullying and insensitive treatment of people who are transgender, focused new attention on this matter.

To avoid stigma and ensure clinical care for individuals who see themselves as a different gender, DSM-5 replaces the diagnostic name "gender identity disorder" with "gender dysphoria" and makes other important clarifications in the criteria. It is important to note that gender nonconformity is not in itself a mental disorder. The critical element of gender dys¬phoria is the presence of clinically significant distress associated with the condition, reported Pride in a seminal article on the subject for ICD10monitor.com.

According to the upcoming fifth edition of DSM-5), people whose gender at birth

is contrary to the one they identify with will be diagnosed with gender dysphoria.

This revision is intended to better characterize the experiences of affected

children, adolescents, and adults.

Pride noted that most medical professionals agree that identifying as transgender

is not a disorder or mental illness/condition. However, persons experiencing

gender dysphoria-anyone who suffers severe distress, anxiety, and depression

due to a strong feeling that they are not the gender they physically appear

to be-need a diagnostic term that protects their access to care and won't be

used against them in social, occupational, or legal areas. When it comes to

access to care, many of the treatment options for this condition include counsel¬ing,

cross-sex hormones, gender reassignment surgery, and social and legal transition

to the desired gender.

According to the DSM-5 Sexual and Gender Identity Disorders Work Group, it was felt that removing the condition as a psychiatric diagnosis, as some had suggested, might jeopardize access to care. But removing stigma is about choosing the right words. Replacing "disorder" with "dysphoria" in the diagnostic label is not only more appropriate and consistent with familiar clinical sexology terminology, but it also removes the connotation that the patient is "disordered."

Unfortunately, Pride pointed out, ICD-9-CM and ICD-10-CM have not changed their

axis of classification from disorder to dysphoria to match DSM-5. If one were

to look up "dysphoria" in the index of either classification, gender identity

would not appear as a sub-term under the main term "dysphoria."

In order to locate this condition, one must continue to look under the main

term "disorder" to find "gender-identity" as a sub-term.

Once you locate the main term and sub-term in the index, coding guidelines

tell us to validate our selection in the tabular section and follow any additional

instructional notes, such as "use additional codes" and excludes 1 and excludes

2 instructions. The code, F64.1 (gender identity disorders in adolescence and

adulthood) provides us with three different instructional notes.

The first is to use an additional code to identify sex reassignment status.

The parenthetical note guides the coder to Z87.890. You should only use code

Z87.890 (personal history of sex reassignment) if the patient has completed

a sex reassignment.

The second instructional note, excludes 1: gender identity disorder in childhood

(F64.2) instructs the coder to not use code F64.1 if the patient's diagnosis

is gender identity disorder in childhood; rather they should use the code F64.2.

The third instructional note, excludes 2: fetishistic transvestism (F65.1),

instructs the coder that the diagnosis of fetishistic transvestism is not included

in the diagnosis of gender identity disorder. However, it is appropriate to

code both conditions if both conditions exist.

It is also important to code all secondary conditions documented by the provider

at the time of the encounter, Pride wrote. These may include depression and

anxiety. See a full listing of depression disorders under Mood Disorders, Categories

F30-F39, and a full listing of Anxiety disorders under Categories F40-F48.

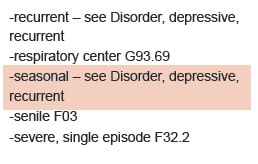

A Code for the Season

With climate change came unprecedented snow and rain to much of the Eastern

United States during the first quarter of this year. So we asked ourselves,

could there be an ICD-10 code for weather-related depression? Well, it turns

out that there is: seasonal affective disorder (SAD).

What is SAD? It is a psychological condition that is normally brought on by

seasonal changes that result in depression. It is most common in women as well

as adolescents and young adults. The exact cause is unknown, and contributing

factors vary between individuals. However, people who live in parts of the country

that have long winter nights and less sunlight are more prone to SAD.

One theory is that decreased sunlight exposure affects the natural biological

clock that regulates hormones, sleep, and moods. In addition, people who have

a history of psychosocial conditions are at greater risk of developing SAD.

SAD is treated with counseling and therapy. Wintertime SAD can also be treated

with light therapy, in which a specialized light box or visor is used for at

least 30 minutes each day to replicate natural light. Light therapy should be

used only under a physician's supervision and with approved devices. Other light-emitting

sources, such as tanning beds, are not safe for use. Some patients may also

benefit from medications such as antidepressants. Healthy lifestyle habits,

such as a healthy diet, exercise, and regular sleep, can also help minimize

SAD symptoms.

Could there be an ICD-10-CM code, given its specificity, for SAD?

We asked Pride to find out.

"My training told me to go to the index first and look under 'disorder,'"

she wrote. "There was nothing there for seasonal affective disorder, so I turned

to the coder's best friend, Google, to learn more. What I found, as stated above,

is that SAD is a form of depression. So back to the ICD-10-CM index I went to

find depression, and there 'depression- seasonal' directed me to 'see disorder,

depressive, recurrent.'"

Next in the index, Pride found disorder, depressive, recurrent, which led her

to the default code of F32.9. Pride wrote that she would be reluctant to code

depression without the physician specifically stating "depression" in his or

her note. This would be a query opportunity to ensure that the patient truly

has depression.

"If my physician documents SAD with depression, good documentation will allow

me to code to the level of severity: mild, moderate, or severe, as well as with

or without psychotic symptoms," wrote Pride. "There are also codes for patients

who may be in full or partial remission. It will be the physician's documentation

that will allow you to code this to the highest level of specificity."

When a definitive diagnosis has not been made, it is appropriate to code signs

and symptoms.

Symptoms of wintertime SAD include:

- Fatigue - R53.83

- Difficulty concentrating - R41.840

- Feelings of hopelessness and lack of interest in social activities - R45.89

- Increased irritability - R45.4

- Lethargy - R53.83

- Reduced sexual interest - R68.82

- Unhappiness - R45.2

- Weight gain - R63.5

The symptoms of SAD can mirror those of several other conditions, such as bipolar

disorder, hypothyroidism, and mononucleosis; therefore, the physician's documentation

of a definitive diagnosis is the key to correctly coding SAD.

Early indications validate not only the specificity of ICD-10, but its breadth as well. Yet the real test is on the horizon, when, less than five months from now, ICD-10 will be required for all HIPAA-covered entities.

Chuck Buck is publisher of ICD10monitor.com and is the executive

producer and program host for Talk-Ten-Tuesdays.