By Kathy Terry, Ph.D., Senior Director, IPRO and Jaz Michael King, Chief Technology Officer, IPRO

Public reporting is, for all purposes, a social sciences undertaking. A consumer-oriented report on healthcare is intended to empower healthcare consumers; educate them on variability, choice and quality; and sell them on the fact that they can impact their own health by becoming better informed.

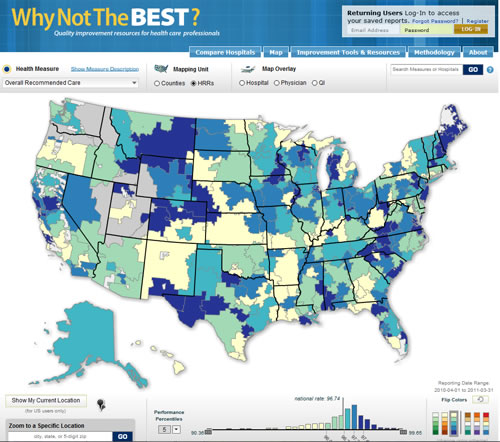

Provider reporting is conversely geared toward stimulating quality improvement and/or measurement for payment reform purposes. This immediately raises the dichotomy of providers needing the exact measurements upon which they are reimbursed contrasted with consumers who may need simpler, aggregate decisions and measurements. A study of the most popular web-based public reports will yield a readily perceived abundance of complexity in the provider report options, driven in no small part by the clinical focus of the reports' designers. In short, more public health care reports have been designed for the provider community than have been designed for the consumer. We propose that the authors of public reports direct greater attention and resources into the consumer audience, and create reports with that very audience in mind rather than simply taking provider directed reports and releasing them to a consumer audience.

From a consumer perspective, public health data is meant to be a data-rich source into which a consumer may dip a yardstick and derive the "best" provider of care. The determination of "best" obviously varies by consumer though the data source has been organized with some necessary pre-conceived fundamental decisions already in place. For example, the efficacy within a measure is dictated by the author of said measure, albeit via statistics or ranking. The measures and sub-measures are ordered across providers as a grouping of better and worse performers. We demark this data with symbols, or literal numbers, representing better and worse performance. We then expect the reader to know which measures are important to them, to rank order the providers of care for the valuable measures, and to interpret our symbols or numbers to arrive at the "answer" of a care provider that meets their need criteria.

We already know that consumers are less than adept at navigating the complexity of the healthcare data. In fact, they subjectively report feeling overwhelmed and confused by an excess of information. The job of the public healthcare data reporter then must also include taking steps to ensure that he/she: 1) knows the intended audience; and, 2) has designed the report with that audience in mind. The extent to which public reports are usable by consumers for provider selection and decision making is determined in large part by how much effort has gone into the design of the report with an understanding of that audience.

Currently, many report cards are designed in a consensus manner drawing on the expertise of various stakeholders, such as healthcare providers, healthcare associations, government officials and epidemiologists. Unfortunately, most report cards produced in the past decade have rarely included consumer oversight or feedback, or have bowed to the demands of the funding agencies and their industry colleagues. This has led to a status quo in public reporting efforts that allows hospital associations, medical societies, and managed care companies (to name a few examples) to have a direct say in what a consumer can and cannot understand, should and should not be told, and exert undue influence on the very visual design of a report.

It is time that public reports take a different tack. Particularly given that the future of healthcare reporting is not diminishing but in fact its public role is becoming even greater. Healthcare public reporting is now moving into fiscal transparency. In September 2013, a provision of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is to publish "transparency reports" that disclose industry payments on a public web site. According to the regulation, the information must be "searchable," "clear and understandable," and "able to be easily aggregated and downloaded." Some financial relationships between physicians and teaching hospitals and the pharmaceutical and medical device industries can benefit patients, primarily those that are related to bona fide basic and clinical research. But as the preamble of the proposed rule states: "Close relationships between manufacturers and prescribing providers can lead to conflicts of interest that may affect clinical decision-making. Increased transparency of these relationships tries to discourage inappropriate relationships, while maintaining the beneficial relationships." Medicare physician data will also be open to qualified organizations to create public health doctor report cards.

Public report cards and data transparency are here to stay. The public will have access to information that can help direct their choice of caregiver and provider. It behooves the public health reporting community to create these reports with the consumer's needs and capabilities in mind, and ensure that the fundamentals of standardization, transparency, design, cognition, and human capabilities are brought together. Public reporting should assist rather than hinder the consumer in their decision-making; it should clarify and not muddy the waters so that the consumer can make the best decision for their healthcare.

For more information on the current works supporting better consumer report cards, look into some of the works supported by AHRQ (www.ahrq.org) including their most recent research call to bring more science to public reporting in addition to RAND, CDC, and others who foster better reporting through greater consumer access. Read the plethora of research that has gone into reporting and is still underway. Question the competency levels needed to comprehend your reports, know your audience, beta-test your site with the target audience, don't be afraid to try new methods for presenting data and remember that consumers need your help: create reports for them, with their capabilities and input!

For more news on public reporting, please visit www.abouthealthtransparency.org. If you would like help with your transparency efforts, please contact us at support@ipro.us.

Kathy Terry, Ph.D., Senior Director, IPRO and Jaz Michael King, Chief Technology Officer, IPRO. IPRO is a national organization providing a full spectrum of healthcare assessment and improvement services that foster more efficient use of resources and enhance healthcare quality to achieve better patient outcomes.

www.ipro.us